Explosive Growth of M2 and Macroeconomic Imbalances

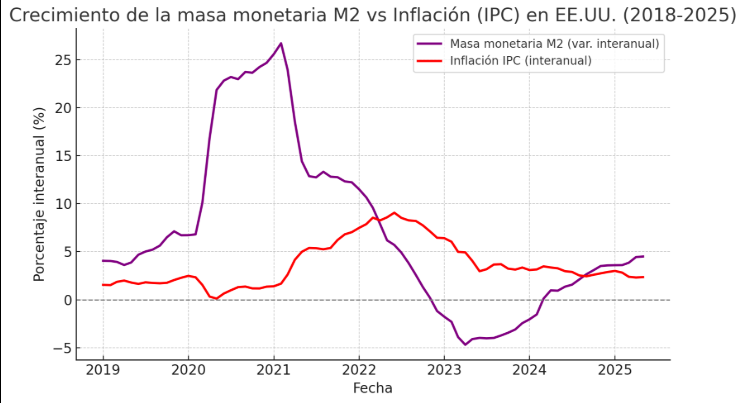

An exponential and indefinite increase in the M2 money supply (cash, coins, and liquid deposits) typically generates significant macroeconomic imbalances. In classical monetary theory (the quantitative equation MV = PQ), if the money supply grows much faster than production, prices will tend to rise sooner or later. In other words, inflation is the typical consequence of uncontrolled money printing, even if it manifests with a time lag. In fact, monetarists like Milton Friedman argue that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” The recent experience in the United States illustrates this relationship: after the massive liquidity injection in 2020–2021 (M2 grew at over 25% annually—an unprecedented rate), inflation surged to 40-year highs around 2022. When M2 expansion later moderated (even turning negative in 2022–2023), inflation also began to decline with a few months’ delay. This aligns with the idea that there is a lag of several quarters between excess money and rising prices, but ultimately inflationary pressure surfaces.

Year-over-year growth of M2 money supply (purple line) vs. CPI inflation (red line) in the U.S., 2018–2025. The unprecedented ~25% annual M2 expansion in 2020 preceded the ~9% inflation peak in 2022. In 2023, M2 even contracted (purple line below 0), anticipating the inflation slowdown to ~3%. (Source: St. Louis Fed FRED)

Beyond the loss of purchasing power (inflation), monetary mismanagement erodes trust in the currency and can destabilize other macroeconomic balances. If M2 growth is permanent and uncontrolled, economic agents may anticipate higher future inflation and demand higher interest rates, causing the currency to depreciate. In extreme cases, the spiral can lead to hyperinflation and monetary collapse. History offers sobering examples: after financing public spending by printing money, Germany (Weimar) in 1923 and more recently Zimbabwe and Argentina suffered catastrophic hyperinflation. In Argentina, for instance, the continued monetization of the fiscal deficit by the central bank led to annual inflation of 276% in 2023. These episodes show that “you cannot print money ad infinitum without adverse consequences.” In short, exponential and sustained M2 growth does create severe macroeconomic imbalances, mainly inflationary, undermining economic stability.

Impact on Capital Markets and Asset Bubbles

The abundant liquidity resulting from monetary expansion tends to inflate capital markets. When central banks flood the system with money, interest rates fall, and investors seek higher returns in stocks, real estate, or other assets, pushing their prices above levels justified by fundamentals. In practice, it has been observed that so-called “global liquidity” explains much of the financial phenomena that precede crises: “stock market rallies, falling bond yields, real estate booms, surges in international capital flows, and even inflation spikes” have all been linked to excess liquidity before 2008. That is, excess M2 can generate not only consumer price inflation but also financial asset inflation (stocks, bonds, real estate).

Several economists argue that in recent decades, money creation has largely become “trapped in financial markets, generating asset inflation rather than real growth.” For example, after the 2008 crisis—and especially in response to the 2020 pandemic—the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet and the money supply to record levels. Between March 2020 and March 2021, M2 grew by about $5.3 trillion (+35%) due to monetary policy and fiscal stimulus. This enormous liquidity flood boosted the prices of stocks, bonds, and homes, contributing to a rapid financial market recovery. In fact, the Fed tacitly acknowledged this effect: since the Greenspan era, its shock-response strategy has been to flood markets with liquidity and “reflate” assets, even if the real economy benefits less. An analysis noted that this pattern has repeated for “30 years: after every shock, the Fed turns on the printing press, asset prices rise, while real growth lags. Excess liquidity does not produce sustainable growth, but market bubbles.”

In practice, after 2020 we saw the S&P 500 and other stock indices reach record highs amid a real recession, and valuations stretch (high P/E ratios, inflated property prices) thanks to cheap money. This “wealth effect” temporarily benefits asset holders but carries risks of violent corrections: when liquidity is eventually withdrawn (e.g., by raising rates to curb inflation), inflated assets can crash. In 2022–2023, with the Fed reducing its balance sheet and raising rates, we saw declines in equities, crypto, and a slowdown in real estate prices—showing that part of their value was propped up by extraordinary liquidity. In short, the indefinite expansion of M2 distorts capital markets: it creates artificial booms followed by sharp corrections, increasing volatility and systemic risk (the so-called “everything bubbles”). Several economists and even voices within the Fed warn that asset prices should be “considered in monetary policy design” to avoid this boom-bust cycle.

The Rise of Cryptocurrencies and Other Alternative Assets

In the current context—marked by distrust in traditional currencies due to money printing—many investors have turned to alternative assets such as cryptocurrencies, gold, or other stores of value. Bitcoin, in particular, was born with the promise of being “digital gold” resistant to inflation due to its limited supply. It’s no coincidence that during 2020–2021—when the Fed aggressively expanded M2 and governments increased debt—Bitcoin's price soared to all-time highs. There’s evidence that Bitcoin acts as a “barometer of global liquidity”: “as global liquidity expands, Bitcoin tends to thrive.” In fact, analysts have quantified that liquidity movements explain up to 90% of Bitcoin's price variation and about 97% of the Nasdaq. The logic is straightforward: “when more money is available, asset prices tend to rise”—including risk assets like cryptocurrencies.

The search for protection against possible dollar devaluation has also driven more people toward crypto. In countries with high inflation or capital controls, the use of Bitcoin and stablecoins has increased (even acknowledged by IMF and The Economist reports). For example, in economies with weak currencies, cryptocurrencies are gaining traction as a store of value. In the U.S., figures like Paul Tudor Jones and Elon Musk have promoted Bitcoin precisely as a hedge against the dollar’s “depreciation” due to massive printing. However, it’s important to note that cryptocurrencies carry their own volatility and risks: part of their 2020–21 surge was driven by excessive liquidity and speculative appetite, and when monetary policy tightened in 2022, Bitcoin dropped more than 70% from its highs. So, even if cryptos are proposed as an alternative in a monetary inflation scenario, they also “feed on the same liquidity,” forming potential bubbles.

In the absence of a brake on M2 expansion and with growing public debt, investors are likely to continue seeking scarce assets like gold, prime real estate, or cryptocurrencies to protect their wealth. This could sustain bubbles in these markets (e.g., speculative crypto surges) until a correction occurs. Some economists warn of the risk that cryptocurrencies may create a parallel financial system that weakens central banks’ ability to control inflation. For now, their size is relatively small compared to the traditional financial system, but their rise is a symptom of growing distrust toward fiat money in uncontrolled monetary environments.

Runaway Debt, Fiscal Monetization, and Long-Term Inflation

The case of the United States is especially relevant: federal debt now exceeds 100% of GDP and continues to grow without a clear containment plan. Although the dollar enjoys reserve currency status, can this infinite debt be sustained without inflation? There is a close relationship between chronic deficits, monetization, and rising prices. When the central bank indirectly finances the Treasury (buying government bonds with new money), it effectively turns debt into circulating money, increasing M2. This was evident after the pandemic: the Fed bought over $4 trillion in Treasuries and MBS, monetizing the massive fiscal stimulus of those years. The result was skyrocketing deficits (15% of GDP in 2020), M2, and, subsequently, inflation (7–9% in 2022, levels not seen since the 1980s).

Economists speak of “fiscal dominance” when monetary policy becomes subordinated to funding the government. In such situations, the central bank’s priority shifts from price stability to sustaining public spending, often resulting in runaway inflation. Several historical episodes show this pattern: during the 1960s–70s in the U.S., the Fed maintained accommodative policies to finance Vietnam and social programs, leading to the great inflation of the 1970s. More extreme are the cases of developing countries where the central bank acts as the government's “cash register”—e.g., Argentina (already mentioned) or more recently Turkey—resulting in galloping inflation. In Turkey, President Erdoğan forced the central bank to cut rates and print money to finance fiscal expansion, leading to high double-digit inflation and a collapse of the lira.

In the U.S., fiscal dominance has not been openly declared, but the risk is growing. Interest payments on the debt rise with higher rates, and if Congress fails to rein in spending (especially on pensions and healthcare), it may pressure the Fed to “run the printer.” In fact, some politicians have already suggested that the government “can print all the money it needs” instead of borrowing. While this may sound alarming, analysts warn that if this view spreads, the Fed could lose its independence, leading to dangerous territory: “printing money ad infinitum” as the easy way out would undoubtedly result in hyperinflation and economic ruin. Monetary theory (Sargent and Wallace, “Unpleasant Arithmetic”) suggests that when markets stop buying public debt, the only way out is to monetize it—which fuels inflation. Ultimately, rising debt and M2 go hand in hand: if the former has no ceiling, sooner or later it will be financed by money creation, and unless money demand grows equally (unlikely), the resulting excess supply will push prices up.

It’s worth noting that for a time, the “trap” wasn’t obvious: after 2008, the monetary base multiplied (due to QE), but inflation didn’t appear because banks hoarded reserves and money didn’t “spill over” into the economy. That experience led some to believe that “you can print without inflating”. However, the 2020–2022 period proved otherwise: when created money reaches the public (via stimulus checks, forgivable loans, asset purchases), and production can’t keep up, prices rise. In 2020–21, ultra-expansive fiscal and monetary policies converged, generating excess demand, supply shocks, and widespread inflation. In short, there is a clear long-term relationship between sustained M2 expansion and inflation—especially when used to finance permanent deficits.

Medium- and Long-Term Outlook: How Does This End?

If the money supply continues expanding without restraint and debt keeps accumulating, the medium- and long-term outlook is grim. In the medium term, the most likely scenario is chronically elevated inflation (above the Fed’s 2% target). This erodes real wages and savings and can anchor high inflation expectations, making it harder to control. To contain it, the Fed would need to adopt very aggressive contractionary policies (rapid rate hikes, liquidity withdrawal), which sharply cool the economy. We already saw a preview in 2022–2023: faced with 9% inflation, the Fed raised the federal funds rate from 0% to ~5% in one year, triggering stock market declines and some banking instability. Fed analysts warn that if inflation remains “unacceptably high,” further action will be required: cutting Treasury purchases and raising rates even more, which “will raise yields, reduce private wealth, increase credit costs, and cool private spending,” possibly pushing the economy into a deep recession. In short, printing too much usually ends in a painful adjustment—either through uncontrolled inflation (if no action is taken) or a severe contraction (if action is taken too late).

In the long run, if policies that irresponsibly expand M2 persist, something even more structural is at risk: global trust in the dollar and U.S. debt. Although it may seem distant today, a scenario of ongoing monetary expansions could lead dollar holders (countries, investors) to flee toward other assets or currencies, weakening the dollar’s status and drastically increasing U.S. borrowing costs (a spiral of devaluation and imported inflation). Some economists talk about the possibility of a “new Bretton Woods” or a multi-currency system if major fiat currencies weaken from over-issuance—for example, increased use of gold, crypto-assets, or a global digital currency. However, before reaching that point, central banks are expected to adjust course to avoid collapse. In fact, the recent contraction of M2 in 2023 (not seen in decades) shows that the Fed hit the brakes when danger became evident. That preventive move has started to slow inflation to more manageable levels. Whether a “soft landing” can be achieved or recession is inevitable remains to be seen, but it shows that the process can be reversed if there is political will.

Conclusion

There is indeed a strong relationship between M2 and medium- to long-term inflation, especially when monetary expansion is used to finance permanent deficits. Exponential and sustained M2 growth without control tends to destabilize the economy: it first fuels financial market bubbles and false prosperity, then leads to high inflation and loss of stability, and finally forces drastic adjustments (either via painful inflation or economic contraction). In the current context, if these trends are not moderated, we may see a combination of stagflation (weak growth with high prices) and financial corrections. However, history and theory offer a clear lesson: eventually, the party must be paid for—either with inflation or with cuts—because there is no such thing as a “free lunch” in unlimited money printing. As research from the St. Louis Fed suggests, even with delays, inflation ultimately follows the path of money supply. Therefore, curbing excessive M2 growth is a necessary condition to restore balance and avoid a chaotic outcome in the years ahead.

Sources: Studies and data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, Dallas Fed, Cato Institute blog, FS Investments analysis, among others. Reports from economists and relevant economic institutions were used to support the arguments.